European fishermen taking the lead in the fight against marine litter

Marine litter and plastic waste have been identified as one of the main threats to the oceans and the marine ecosystems, to the point that many have voiced that by 2050 there will be more plastics than fish in our oceans. Scientists have estimated that up to 12 million tonnes of plastic is entering our oceans every year. Fishermen are deeply concerned since fish stocks heavily depend on a healthy marine environment. Europêche members, aware of the problem, increasingly getting involved in environmental schemes to help combat the growing issue of marine litter and encourage fishermen across Europe to participate in recycling and clean up initiatives.

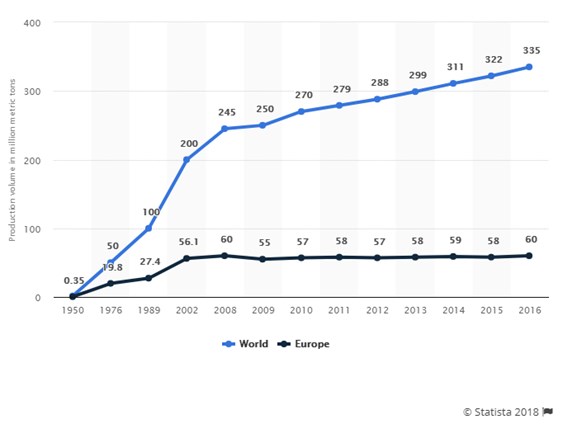

There are many factors that have contributed to a rise in marine litter over the last 20 years including a significant increase in plastic production (as reflected in the figure below), poor waste management and general public attitudes towards littering. However, the problem is accentuated in other parts of the world, since a recent scientific report revealed that 88-95% of the global load into sea comes from ten rivers, 8 in the Asian and 2 in the African continents, acting as a major transport pathway for plastic debris1.

This has major implications for human health, marine ecosystems and maritime economic activities. The European Commission (EC) estimates that the economic damage to EU fishers2 ranges between €60 million and €300 million per year.

Regarding fisheries waste, a new report claims that 640.000 tonnes of fishing gear is thought to be lost or abandoned in the oceans every year, making up less than 10% of all marine litter. Some of these derelict fishing gears continue catching fish even if not man-operated, also known as, ‘ghost fishing’. Europêche argues that these figures are not new since they come from a very old FAO report from 20093 based on non-comprehensive information that does not allow for any global estimates, as recognised by the authors.

These figures, therefore, do not reflect the current situation, at least in the EU. Javier Garat, President of Europêche, stated: “In the EU we have a completely different picture. For instance, while FAO will only adopt voluntary guidelines on marking fishing gear in July this year; in the EU it is mandatory for fishermen since 2009 to mark and identify their gears, have adequate equipment on board to retrieve lost gears and immediately inform coastal authorities in case of loss. I know enough examples of fishermen looking for their damaged or lost nets for three days at sea since a gear can cost up to €50.000. Most nets are not deliberately discarded; their loss result from gear conflicts, storms or strong currents. The problem is that there are 40-50 year old gears at sea only being recovered nowadays.”

Apart from the strong European regulatory framework, fishermen are voluntarily participating in several programmes across the EU not only to better take care and recycle the garbage produced on board but also to bring ashore derelict fishing gear and passively fished waste, Europêche says. Our companies are also collaborating with universities in order to improve the tagging of fishing gears and enhancing on board best-practices to promote waste free fisheries as well as developing biodegradable materials and using non-entangling fishing aggregated devices (FADs).

Javier Garat commented: “Fishermen are extremely involved in such innovative initiatives to prevent, recover, reuse and recycle of fishing gears. As an example, thanks to their partnership with KIMO, over 500 fishing vessels landed 2500 tonnes of waste from the sea between 2011-2016 which will no longer be affecting the marine environment, let alone the economic activities, and are recycled into new valuable products as we speak.”

Finally, as a result of the new Directive on Port Reception Facilities proposed by the European Commission in January this year, the EU plans to require all fishing vessels to pay a fee to the port or harbour irrespective of whether they deliver any waste or not.

Javier Garat concluded: “Fisheries is part of the solution as our trawlers mostly clean up other people’s waste and the EU should continue incentivising these good practices. The introduction of a discriminatory fee to fishermen for waste they do not generate is not the way to motivate the industry in continuing with the good work in combating this global problem.”

Figure 1: Global plastic production from 1950 to 2016 (in million metric tons).

Ends

Europêche represents the fisheries sector in Europe. Currently, the Association comprises 10 national organisations of fishing enterprises from the following 8 EU Member States: DE, ES, FR, IT, MT, NL, LV, PL.

Press contacts:

Daniel Voces, Managing Director of Europêche: +32.2.230.48.48 daniel.voces@europeche.org

- Schmidt, C., Krauth, T., & Wagner, S. (2017). Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea. Environmental science & technology, 51(21), 12246-12253.

- Caused through fouling of propellers, blocked intake pipes and valves, snagging of nets, silting of cod ends and contamination of catch.

- Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T., & Cappell, R. (2009). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (No. 523). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Sources: Europeche

Attachments:

Tags: marine litter, plastic, transport pathways, european commission, fishing gear, ghost fishing, marking, fao, waste free fisheries, fads, KIMO, Directive on Port Reception Facilities